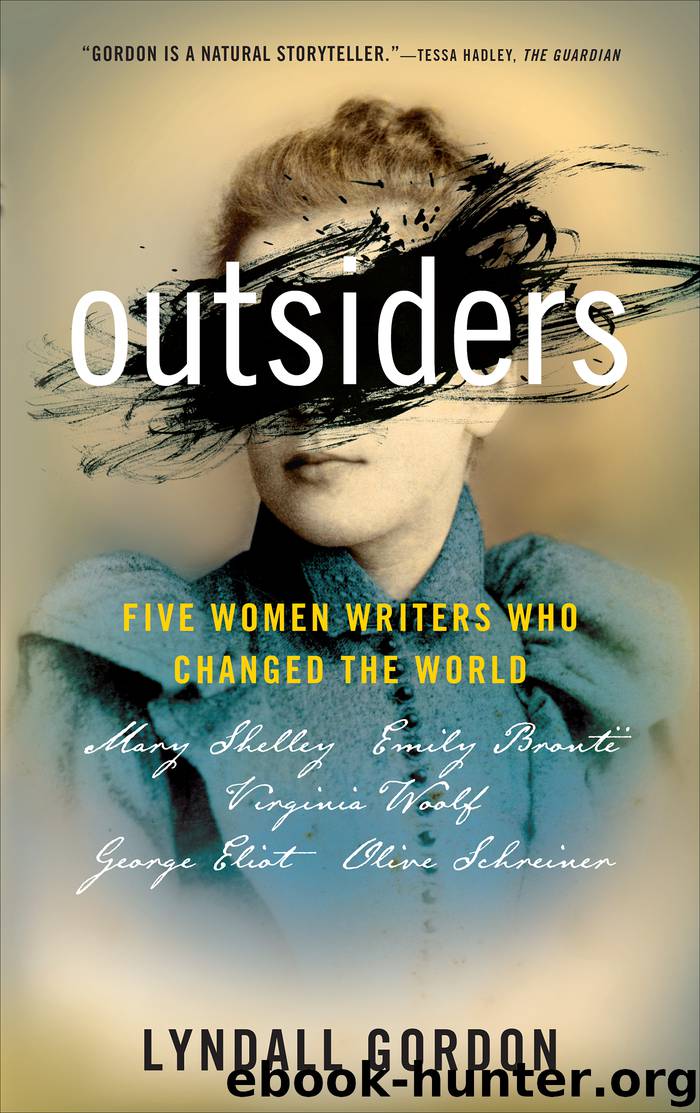

Outsiders by Lyndall Gordon

Author:Lyndall Gordon

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Johns Hopkins University Press

Published: 2019-03-19T16:00:00+00:00

As a child, Olive asked a Basuto woman if she believed in God.

She’d heard of the white men’s God, the woman replied, but she did not believe in him.

‘Why?’

‘Because they say he is good, and if he were good, would he have made woman?’

She then poured out her bitterness at her subjection. Olive watched another tribal woman be beaten by her husband – her legitimate owner, who had bought her with cattle – then silently pick up her baby and, tying it to her bleeding back, return to work. Such women were fatalistic – this was the way the world was.

The immediate catalyst for her early loss of faith was the death of her baby sister Ellie (Helen) in 1864.

Olive and baby Ellie had a special bond, common in big families where a mother’s attention is stretched thin. Olive would look back on this child as proof that perfection did exist. She slept with the body before Ellie was buried. She dedicated her unfinished novel From Man to Man to ‘MY SISTER LITTLE ELLIE WHO DIED, AGED EIGHTEEN MONTHS, WHEN I WAS NINE YEARS OLD ‘Nor knowest thou what argument / Thy life to thy neighbour’s creed hath lent’. In ‘The Child’s Day’, a ‘prelude’ to this novel,* a Karoo child of five called Rebekah – an ‘incarnation’ of Olive herself – comes upon the body of a new-born sister (one of twins) in a back room, and finds the baby’s hand cold. Little Rebekah is treated with impatience by a servant who can’t take in the child’s feeling, similar to that of the philosophic child Waldo in The Story of an African Farm, when he awakens to mortality.

Where George Eliot, in her outcast years, had developed a rational kind of sympathy (requiring, she tells us, a hard-won justness towards people like Maggie Tulliver’s repressive aunts or Dorothea Casaubon’s unresponsive husband), Olive Schreiner came to sympathy as a child; she felt spontaneous compassion for victims. In this, she herself bears out the belief, put to the test in Frankenstein and Wuthering Heights, that human nature is wholesome until it is corrupted.

As a child, sympathy came to her as a renegade emotion that could not accommodate a God who determines the undeserved death of innocents. She also deplored Christianity’s lack of concern for animals as sentient creatures. When Olive was losing her faith at the precocious age of ten, she could still take comfort in the non-violent message of the Sermon on the Mount. But her mother was not pleased.

At twelve, when her parents could not afford to keep her, she was sent to live in Kruis [Cross] Street, Cradock (a Karoo town in the dry interior of the eastern Cape) with her older brother Theo. The house had a dung floor and a yellow-wood ceiling, and the kitchen, according to rural custom, was painted turquoise to repel flies. An older sister, Ettie (Henrietta), kept house. Physically, Ettie and Olive manifest the difference of their parents: Ettie fair, broad-faced, rather Wagnerian; Olive, five years younger, small and glowingly dark like their mother.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12392)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7763)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7346)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5775)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5771)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5448)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5096)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4944)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4732)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4574)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4556)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4540)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4449)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4108)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4033)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(4010)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(4004)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3986)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3853)